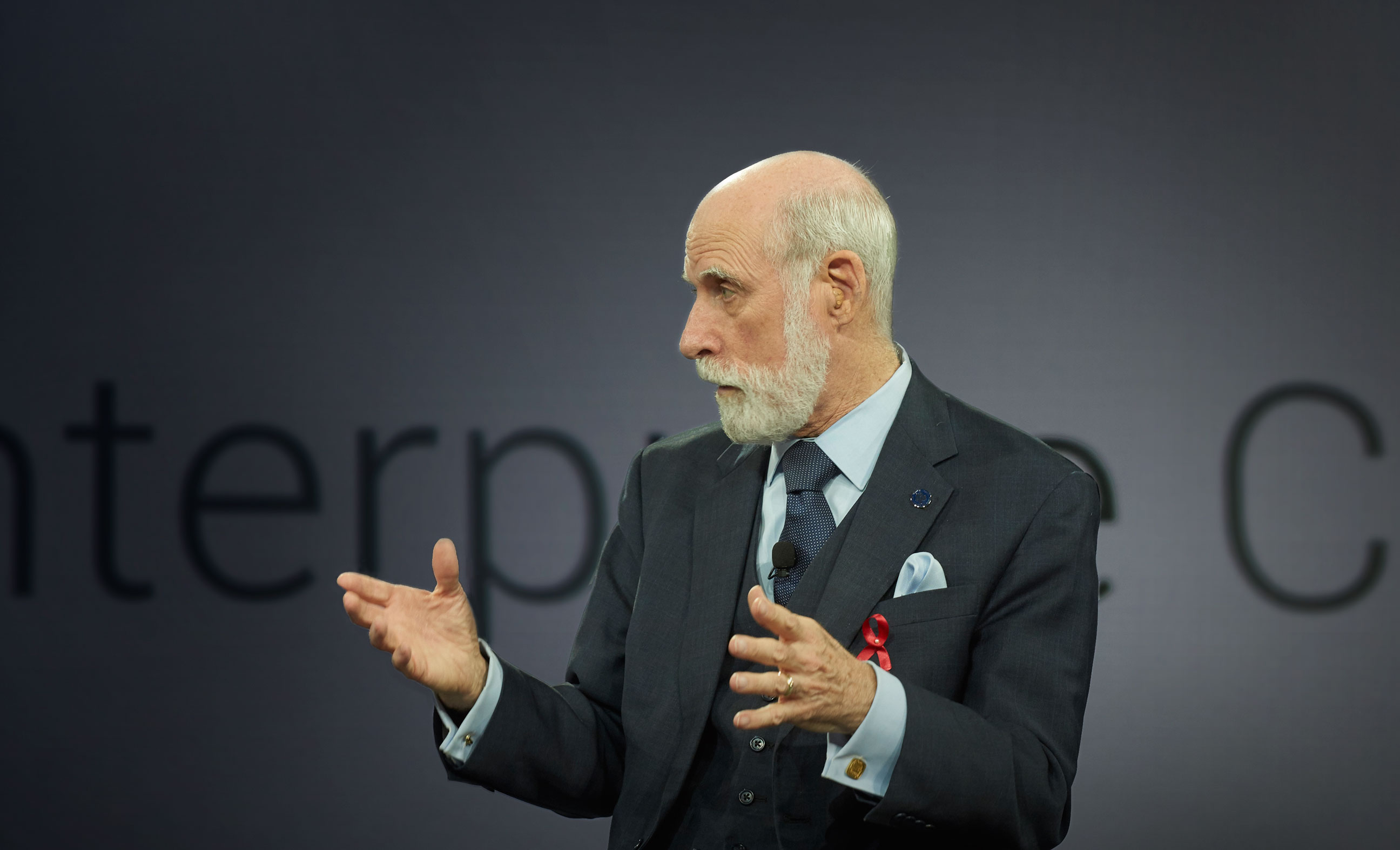

Vint Cerf: past, present, and future of the internet

Google, the Cloud, or podcasts would not exist without the internet, so it’s with an incredible honor that we celebrate our 100th episode with one of its creators: Vint Cerf.

Listen to Mark and Francesc talk about the origins, current trends, and the future of the internet with one of the best people to cover the topic.

About Vint Cerf

Vinton G. Cerf is vice president and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google. He contributes to global policy development and continued spread of the Internet. Widely known as one of the “Fathers of the Internet” Cerf is the co-designer of the TCP/IP protocols and the architecture of the Internet. He has served in executive positions at MCI, the Corporation for National Research Initiatives and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and on the faculty of Stanford University.

Vint Cerf served as chairman of the board of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) from 2000-2007 and has been a Visiting Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory since 1998. Cerf served as founding president of the Internet Society (ISOC) from 1992-1995. Cerf is a Foreign Member of the British Royal Society and Swedish Academy of Engineering, and Fellow of IEEE, ACM, and American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the International Engineering Consortium, the Computer History Museum, the British Computer Society, the Worshipful Company of Information Technologists, the Worshipful Company of Stationers and a member of the National Academy of Engineering. He has served as President of the Association for Computing Machinery, chairman of the American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) and completed a term as Chairman of the Visiting Committee on Advanced Technology for the US National Institute of Standards and Technology.

President Obama appointed him to the National Science Board in 2012. Cerf is a recipient of numerous awards and commendations in connection with his work on the Internet, including the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, US National Medal of Technology, the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering, the Prince of Asturias Award, the Tunisian National Medal of Science, the Japan Prize, the Charles Stark Draper award, the ACM Turing Award, Officer of the Legion d’Honneur and 29 honorary degrees. In December 1994, People magazine identified Cerf as one of that year’s “25 Most Intriguing People.” His personal interests include fine wine, gourmet cooking and science fiction. Cerf and his wife, Sigrid, were married in 1966 and have two sons, David and Bennett.

Also, he’s awesome.

Cool things of the week

We interviewed Vint Cerf!

Interview

Question of the week

Who will you interview for episode 100?

- Vint Cerf.

Transcript

show full transcriptSPEAKER: Join us now as we proudly celebrate the 100th episode of the Google Cloud Platform Podcast.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

FRANCESC: Hello and welcome to episode number 100 of the weekly Google Cloud Platform Podcast. I am Francesc Campoy, and I'm here with my colleague, Mark Mandel. Hey, Mark. How are you doing?

MARK: I am so excited.

FRANCESC: [LAUGHS] Why, I wonder?

MARK: We have Vint Cerf on our podcast.

FRANCESC: Yes. We just--

MARK: I'm so excited.

FRANCESC: We just finished an amazing, amazing interview with Vint Cerf, one of the fathers of the internet. And I feel like there's no intro necessary. There's no cool things of the week. I mean, the cool thing of the week is we interviewed--

TOGETHER: Vint Cerf.

FRANCESC: So I feel like we should just give all of our audience this present and just enjoy.

MARK: Yeah. It's a long interview, so we want to make sure you have enough time to listen to it all. So yeah. Let's just jump straight into it.

FRANCESC: This is all for you. Enjoy.

So it is with an incredible honor that we are welcoming today Vint Cerf, one of the fathers of the internet, as Wikipedia says, to the Google Cloud Platform Podcast to celebrate episode 100. Vint, thank you so much for joining us today.

VINT: I am just delighted. This is the kind of conversation I live for, so I am looking forward to the questions and the repartee.

FRANCESC: Yeah, I'm incredibly excited because I've been a huge fan for a very long time, obviously. But also because I took a selfie with you three years ago in a cafe in [? Monteview. ?] And since then, I've always wanted to have a longer conversation. So all of these podcasts were just an excuse to get to meet you again. So thank you for joining us.

VINT: Well, I really-- as I say, I really am delighted. And there is so much to say about how Google has transformed its world in the Google Cloud platform. It's something that we can all be proud of, but also recognize the huge amount of work lying ahead to make it more useful for our own internal purposes and for the users that we have all around the world.

MARK: Cool. Well, before we get stuck into all that stuff, because, oh my god, I'm so excited. If anyone hasn't had the pleasure of knowing, reading, or hearing about Vint Cerf, Vint, do you want to give us a little bit about you and your background and what you do at Google?

VINT: Well, sure. I'd be happy to do that. I've been at Google since 2005. I joined as Vise President and Chief Internet Evangelist. And I confess to you that I did not ask for that title. I was asked what title did I want, and I said, Archduke.

And Larry and Eric and Sergey ran off, and they came back, and they said, you know, the previous Archduke was Ferdinand, and he was assassinated in 1914, and it started World War I. Maybe that's not a good title to have. Why don't you be our Chief Internet Evangelist? And I said, OK. I can do that, considering I've been doing it for about 35 years before I joined Google.

So of course, before that, I had many roles to play in the evolution of the internet. And I'd like to think I still have a role to play. Eric Schmidt, our executive chairman, pointed out to me that I wasn't allowed to retire. And I said, why not? And he said, because you're only half done. There's still 3 and 1/2 billion people to convert to get up on the internet. And he's right about that. There is still much work to be done.

FRANCESC: Cool. So that actually ties up really well with one of our first questions, which is so what does Vint Cerf do day to day?

VINT: Well, fortunately, my life is not repetitive. Every day is new and different. I have many meetings. Like today, for example, I was at the Inter-American Development Bank for the morning, meeting with people who are interested in making major investments in infrastructure.

They're trying to understand how they can take actions that will improve access to the internet in the developing world, and they're trying to understand what conditions need to be in place so that any investment they might make will have productive results. And in that case, of course, we're worried about the entire ecosystem surrounding the implementation and operation of the internet, and the creation of new applications that will be useful to people locally, in local languages, in addition to facilitating visibility for companies in the rest of the world, which is something we try to do for people who are advertising their products and services.

So I spend a lot of time, both here in Washington and on the road, on policy-related matters that have to do with the use and abuse of the internet. That's another big theme, is that once you put the general public up on the internet, you get what you sort of deserve, which is the general public, including people that don't have your best interests in mind.

And so a big issue for us and others that offer services on the net is how to deal with people who inject bad information onto the net, or who commit fraud, who bully people, who distribute malware. There are a variety of things that we are well aware of, thanks to headlines, that are harmful in the network environment. And so our job is to do everything we can at Google to limit the kinds of damage that can be done, while at the same time enhancing and enabling all kinds of very positive applications on the network.

So our search engine is very much a tool that people use to find out what's available on the network. What products and services are there, not just on the net, but in general nearby areas or even around the world. So part of my job is to help people think their way through what conditions they need to create-- if they don't already exist-- to both build and operate pieces of the internet and then construct applications on top. How to we enable it to be beneficial to the people who are trying to use this far-flung global system.

I'm in the research group, it turns out, and report up to John G. and Andrea, so I also get exposed to a lot of the things that are going on the research side, especially in artificial intelligence, machine learning, quantum computing, and things like that, which are well beyond my personal capability, but I'm fascinated by.

On top of which, Google has been very generous with my time, and so I do outside activities that contribute also to this. So I sit on the National Science Board, overseeing the National Science Foundation, which is doing a great deal of research in all the various sciences, including computer science.

I had been chairman of the Americas Registry for Internet Numbers until the beginning of this year, which oversees the allocation of internet address space to people in the Caribbean and North America. I was chairman of the internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers from 2000 to 2007, again, a major component of the internet infrastructure, managing the domain name system and top-level IP address allocation.

Google has been very willing to allow me to spend time in the internet space in one way or another, whether it's directly associated with Google, or more generally with the internet infrastructure. And so I'm very grateful for that.

MARK: Fantastic, There's so much stuff to unpack there. I think that you clearly do so much amazing things. Why don't we sort of go back a little? I'm very curious about the history of some of this stuff.

It's actually kind of hilarious. We were talking about this earlier. Francesc is in Paris, France. I'm currently in Melbourne, Australia. You're in Washington. The very network and infrastructure that you fathered, for lack of a better term, makes this whole thing possible. But you are known as one of the fathers of the internet, so thank you very much for that, making our jobs all possible.

VINT: To the extent that this has been beneficial, I thank you for the credit. To the extent that some damage has been done, I refuse to accept the responsibility. [LAUGHS]

FRANCESC: Thank you for the goo parts.

MARK: That seems fair enough. There you go. Yeah, thank you for all the good parts. But I'm super curious. I mean, when you were working back at the origin state, many people consider the internet sort of-- for those of us who have become used to it and who have access to it, become almost a human right or a requisite part of existence. Did you ever see that in the pathway of this distributed network you were building?

VINT: Well, I certainly never anticipated the notion that access to the internet might be considered a human right. And as you may know, I have published at least one op ed that suggested that that was not a good formulation. I'd like to come back to that. But let's go back to the origins of this system.

It was originally funded by the American Defense Department. My partner in the design is Robert Kahn, who at the time was at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. This is way back in late '72, early '73 of the previous century. God, that sounds like a long time ago. And it was, actually.

So Bob had this idea that open networking would be a good thing. That the packet switching technology of the ARPANET project could be replicated in multiple networks, some that are mobile radio, some over satellite, some over dedicated wireline. And that these multiplicity packets which networks needed to be interconnected in a way that create a commonality. And the only way we could do that was to develop a set of protocols that would let these disparate packet switch nets look like one gigantic network, although made up of many nets. So the internet is a network of networks.

We developed the protocols and the concepts to do that in 1973 and published a paper in 1974. Developed the detailed specs for the protocol in late '74. Started the implementation in 1975. Ran through a series of iterations, four of them or so. Stabilized the design in 1978. Started it implementing it on many different operating systems. Turned the system on, on January 1, 1983.

Now, you might say, did you have any idea that it was going to be global in scope? The answer is absolutely. Because we imagined this would be needed by the American Defense Department for command and control. That means it has to work no matter where the Defense Department deployed, which meant it had to work everywhere in the world.

So we were already thinking in global terms at the time that this design was being done. We actually didn't quite get it right. We thought that a 32-bit internet numerical address space would be enough at least to do an experiment. So we designed the system to have 4.3 billion terminations.

Now that, I think, might have been more than there were people in the world at the time we were doing this work. However, we ran out around 2011. Fortunately, the engineers who do the standards for the internet and the Internet Engineering Task Force could foresee that we were going to run out and designed a new format for the internet packets that had a 128-bit address space.

Now, we're not talking about domain names, which are alphanumeric. For example, Google.com. We're talking about an underlying numerical address space. Sort of like phone numbers, although the analogy is sometimes it doesn't work, but it's similar in nature.

So a 128-bit address space is also referred to as IP version 6, Internet Protocol version 6, which gives you 3.4 times 10 to the 38th addresses, which is a big number. Google has been at the forefront of implementing IPv6 for the various applications that it supports, and it will continue to support both v4 and v6 address spaces until such time as v4 seems to be no longer needed.

So we are among the good guys who've been pushing v6 implementations. It's probably got to about 30% worldwide on average, although there are some networks that are 100% capable of doing both the older version 32-bit addresses and the 128-bit. And there are some networks that haven't done anything yet at all. So there's still work to be done.

The internet of things, which is threatening to overwhelm us, in terms of numbers of devices on the net, could have as many as 50 billion devices in the system by the early 2020s, which we'll definitely need the IPv6 v-6 expanded address space. Mobile phones also are dependent on this. The thing called LTE, or Long-term Evolution, which is sometimes called 4G, also makes use of IPv6 address space. So you can see this proliferation of devices is driving that.

Finally, with regard to internet of things-- it's something our company cares a great deal about-- there are both the production of these devices at Nest, for example, and at Google, and there is the Cloud component of this, which is helping to monitor the devices, to provide artificial intelligence applications through those devices, such as Google Assistant by way of Google Home, or by way of the Pixel, or the Chromebooks, or other kinds of equipment that Google makes.

So we are now faced with a proliferation of devices and also a great deal of concern for safety and security, privacy and reliability of this increasingly large system of devices all interacting with each other. And so that's certainly going to be a challenge, not only for Google, but for all the other parties who are beginning to participate in the internet of things. There's lots more to be said there, but let me stop there and just say that there's lots that I've been finding myself engaged in because of this huge investment that we and others are making in internet-enabled devices.

FRANCESC: So to go back a little bit to the more society side of the internet, I'm curious about were you expecting these huge changes in society? Literally, the internet has changed the way we do things. We communicate, we work, we do everything. Was that something that you expected, too?

VINT: Yes. And I can prove this, in the following sense. In 1992, I became the founding president of something called The Internet Society. And why did we call it that? Because I believed that a society would emerge out of the internet, and indeed it has.

That society may not be one that we like 100%, and this is what happens when you create new infrastructure. People find ways to use it and to abuse it. It's like cars and the roads that they drive on. People get drunk, and they drive the cars and run into each other and run into things and kill themselves or harm other people.

The internet has its downsides. It has lowered the barrier to access to information. It has lowered the barrier for expression to practically zero. And I've always thought that was a good thing. That we want more ability for people to both express themselves and to share what they know and to find out what other people are willing to share.

But at the same time, we also have to recognize that there are people who get on the net and do not have the rest of the society's best interests at heart. So we worry about fraud. We worry about false information or misinformation or so-called fake news and things like that.

We worry about malware that people create and propagate through the network and cause harm to devices that are attached to the network, or essentially grab control over those devices and turn them into what are called bot nets, which are robotic networks that can then be used to generate denial of service attacks or to generate spam or do other kinds of things that are potentially harmful.

So this huge global system, which has literally, I would say, millions of networks, including the local one that you are on at home, for instance. And then the big, gigantic globe-spanning networks of the telcos and the cable co's. This system is like every other infrastructure, capable of being abused. And we're experiencing the effects of the society which is emerging out of this technology.

So now we have to struggle with protecting people against harmful experiences online. And sometimes we can build technical means of protecting them, detecting malware, for example. Defending against denial of service attacks. Filtering out spam, which we do very well in our Gmail service.

So we have these technical means of protecting people. Two-factor authentication to keep accounts from being seized or hijacked. But you can't assure that you can prevent all harmful acts from occurring on the net through technical means. And so you also have to build in mechanisms for saying, if we detect or catch you doing some of these bad things, there will be consequences.

And here now we get into international agreements. Because the network is global in scope, and the perpetrator of harm may be in one jurisdiction, and the victim in another, across international boundaries. Which immediately says we need to have cooperative interactions among the countries that are part of the internet environment. There are just so many issues here that we have to cope with, not only as Google, but also more broadly as citizens in the online environment.

So I'm actually spending a lot of my time asking questions about policy, for example, and how it can be implemented and enforced. Where does the policy come from? Can we use multistakeholder processes to establish policy and then use law enforcement and trade agreements and other kinds of things to enforce safety for the people who are online, to enforce their privacy to protect them against the various forms of abuse.

I might point out one more thing, as long as I'm rattling on here, that this lowering of barrier for speech means that you and I and others on the net-- the 3 and 1/2 billion or so that we believe are online-- now have an additional challenge before them, and that is to think critically about what we're seeing and hearing in this environment because it's easy to inject malware, or easy-- I should say, inject false information or mistaken information in the system. And our search engine finds both the good stuff and sometimes the not so good stuff.

And so as users of the network, we suddenly inherit this responsibility for thinking critically about what we're actually seeing and hearing, and questioning where did it come from. What's the basis for my belief that this is useful versus bad information. I think a lot of people are a little uncomfortable that they suddenly inherited this responsibility. But indeed, if you want to use the network to best effect, you actually have to think critically about that.

MARK: So I think this segues into an interesting topic as well, when we're talking about the safety of the internet, both from malware and also from a societal point of view. How do you think this affects either net neutrality or the idea of net neutrality? Does it have an impact on how we should be thinking about that?

VINT: So this is a very good question. The term net neutrality, as I'm sure your listeners know, is used in different ways in different parts of the world. So we have to be careful about the use of the term and ask, OK. In what context are we asking the question?

In the United States, for instance, during the early 1990s, there were about 8,000 internet service providers. This was a dial up system. And to reach a particular internet service or service, you just dialed a particular number that got you to a modem bank. If you didn't like the service, it was easy to switch. You just dialed a different number. And so there was quite a bit of user choice in terms of access to the internet.

Along comes broadband, and suddenly, there are very few providers of broadband service. The telcos, the cable co's, and that's about it. Although in recent times, we're starting to see wireless services increasing in their data rates, so that they could be considered broadband as well.

So during this period, roughly in the very late 1990s early 2000s, in the US, if you were looking at broadband service as a consumer, you didn't have very much choice. If you were in the rural parts of the country, you had zero choice for broadband. No one was providing that service. If you were in the suburban areas, you might have a choice of either a telco or a cable co, and in the urban areas, you might have a choice of two suppliers of broadband.

So not everyone was uniformly able to get competitive access to broadband service. This is still a problem today. And the absence of enough competition and choice for the consumers, there's always the risk that a monopoly supplier will, in fact, interfere with people's freedom to use the network way they want.

For example, if you're in the vertical business providing video services in addition to underlying internet service, it might be tempting to interfere with a competitor's video service going through the internet channel. And in fact, there were some indications of this kind of bad behavior on the part of some of the broadband carriers who would inhibit voiceover IP, or would interfere with streaming video in order to induce customers to use their service or possibly to interfere with intermediate carriers who were trying to carry traffic, and who were getting squeezed, and therefore, quality of service suffered.

So we have what I think are fewer choices as consumers. And as the choice goes down, then the risk factors go up. And so now you need some regulation in order to assure that consumer interests are protected. So the net neutrality rules mostly, as I see it in the US, are intended to limit the ability of a broadband internet service access provider to interfere with what you do with the network. Where you go on the net, what products and services you exercise. That's why it's been a big issue here in the US.

The ability of the Federal Communications Commission to step in and defend the user's choices was limited for a time because there was a choice made by the FCC to treat the internet as an unregulated information service. And subsequently, there was an attempt to put in principles for net neutrality or defense against practices that were anti-competitive.

When they tried to-- when the FCC tried to enforce those principles, it was told by the Supreme Court that you didn't have a legal basis for exercising that control, because the FCC had decided that the internet was an unregulated service. So they had no basis for regulation. This caused the FCC, under Tom Wheeler, to shift the internet service into Title II, which is the telecom title, reinstantiating the FCC's ability to regulate.

And now, of course, under the new administration, Ajit Pai, the current chairman, is trying to undo that particular decision and to put the internet back into an unregulated state, which means that there would be no legal basis for protecting users whose freedom of choice may have been harmed by a non-neutral provider.

MARK: So at this stage in the US, there's some uncertainty about protecting user interests. In other parts of the world, there may be enough competition so the users can simply choose a different carrier or different internet service provider in order to get service and thereby use competition as a balancing effect. Here in the US, there isn't enough competition, and so regulation seems to be the only alternative.

FRANCESC: That is really concerning. I was actually not aware of the last part, so thank you for sharing that. Since you're already mentioning access to the internet on other parts of the world, I'm curious about since you were able to predict a little bit that the internet would be a global thing, and it changed the world, do you think that having the rest of the world get access to the internet will change it again, or it will be more of a progressive thing?

VINT: Well, it will certainly change it, for one thing. Half the people in the world don't have access yet. And we already know some of the things that have happened, positive and negative, for the people who are already online. The reason I think it will change, although maybe not in predictable ways, is that the people who will get access next, the next billion or two, probably will get access through a wireless method rather than a wired method. They probably will have smart mobile phones, which now are heavily populated all around the world.

They will have needs which have evolved over time. And so those of us who have been online for-- especially in the broadband world-- let's say, for the last 15 years or so, have experienced the internet largely through laptops. And now, of course, the rest of the world is going to experience the internet through smartphones and possibly other smart devices, as the internet of things continues to deploy.

So their experiences and their needs for service may turn out to be quite different from what we experienced 10 or 15 years ago. The consequence of that is that there is opportunity everywhere, and on top of which, solutions to issues arising in this vastly increased demand may actually come from the people who are new to the internet, as opposed to people who've been around for a while.

Don't forget that intelligence is uniformly distributed around the world, but a lot of the smart people may not be able to exercise their intelligence to good effect with regard to internet, because the opportunities may not be there. There may not be incentive for investment, for example. They may not have the moral equivalent of venture capital and risk taking, which is endemic in the Silicon Valley, less so in other parts of the world. So I think the newer inductees into the internet family will experience new needs and come up with new requirements, but also new solutions, which may propagate back into the rest of the internet.

So to give you an example, in China, I've been told, in the eastern part of China, don't bother carrying cash. Everything is paid for with the mobile. Even the beggars hold up their little mobiles and say, take a picture of this little quad symbol and transfer money to me. Which is-- that has to be a very weird feeling. You know, somebody who is begging using a smartphone. Saying, wait a minute. You have a smartphone, and you're begging. How does that not work?

But I will say, in India, for example, where digital identities have been issued to some 800 million people, these people have suddenly become visible to the government, whereas before they were not. And they become eligible for benefits that they couldn't get before. Estonia only has a million and a half people. They are heavily networked and internet enabled as any country in the world.

And they're an interesting place to look. Because when 100% of the population is online with digital identities and everything else, there are things you can do, relying on the fact that 100% of the people have access, as opposed to a country like the US, where maybe 80% have access, and the other 20% don't, so you have to accommodate that statistic.

So here we are with examples of places that are deeply embedded in the internet system and in digital applications. It's like explorers going out into a territory which nobody has been in and reporting back to us what's out there, so we don't have to make the same mistakes they do.

MARK: Speaking of explorers, I'm thinking possibly way in the future or possibly not, depending on some of the advances that we've been seeing lately around interplanetary and space travel. When you built the internet as it was, were you thinking about possibly interplanetary networks, having space stations that currently orbit the earth, and having them communicate backwards and forwards? Was that something that you built into the protocol and design of the system, or do you think it's going to change going forward?

VINT: Actually, I know it's going to change, because we're already there. We're operating an interplanetary system. And the TCP/IP protocol did not work. And when I say we, I'm speaking of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at NASA, plus now many of the other NASA laboratories.

I started work on an interplanetary extension of the internet in 1998 at JPL, and we very quickly realized that the TCP protocols were designed in a low-latency context with relatively high reliability. In space, you have the inverse of that. You have low reliability, and you have variable and often very long latencies, we're talking about hours to days.

So your ping is not your friend here, in terms of network management and interaction. You don't really know how long it's going to take for an interplanetary packet to get to its destination. It may have to hop through multiple sites, from Earth, to Mars, to Jupiter, to wherever.

So we had to develop a whole new suite of protocols, which we call the Bundle Protocol, which is an instance of what is called delay and disruption tolerant networking. So in fact, we have fought our way through that. We've now deployed, first, a prototype system on Mars, and now we've deployed the most recent and fully standardized protocols on the International Space Station. And we hope those same standardized protocols will be on board spacecraft which will be going to Mars and elsewhere during the 2020s.

So in that particular case, we had to accept that the original design simply was not capable of accommodating the kinds of lossy, long, highly variable delay that the space environment presents us with. And so that's why we designed a new system. But It is interoperable with the rest of the internet. It's just that the rest of the internet isn't organized around that suite of protocols.

FRANCESC: So that is amazing. Sincerely, I'm really impressed with that. I'm wondering now, is there something else other than TCP/IP-- which clearly there is-- are these protocols still based on the end to end principle? Could you tell us a little bit what is the end to end principle, and is that something that you are forgetting now to go interplanetary, or is it actually even more important?

VINT: Well, end to end basically said, you put something into the network, and in theory, it should pop out looking exactly the same on the other end. And you rely on the fact that the packets aren't being altered or modified in between. This is still very much a principle that lots of us would like to hang on to as part of the internet characteristic.

The reason that's so valuable is that if you're building protocols that are at the edges of the network, building up from the basic internet protocol, this end to end principle helps a lot. Because you can assume that what was put in by some party in some distant part of the network arrives intact at the other end.

Now, there are ways of assuring that by using cryptography, for example, or digital signatures and other things to assure integrity of the end to end concept. There have been some, let me say, breaks in this end to end notion. For example, as the internet deployed commercially in the late '80s and early '90s, we saw corporations building firewalls around their corporate assets in order to try to protect against attacks coming through the network to their targeted corporate infrastructure.

That actually introduced, down in the guts of the network, something which potentially interfered with the end to end principle. Because, in fact, the packets for getting examined. They might be destroyed. They might be perhaps not altered, necessarily, although there's the possibility of doing what's called network address translation, which in fact does interfere with the end to end principle, because what may be sent on one end is not how it looks when it's received on the other end. So I've never been a big fan of this whole network address translation because it violates the end to end principle.

I think that over time, we will ultimately discover that firewall motions are inadequate to protect against hazards on the network. And then ultimately, every device on the network has to be able to defend itself. When the original design was done, we assumed that anyone could talk to anyone else because we didn't know who would usefully be able to do that. But we also said, you don't have to talk to anybody if you don't want to.

And so if you receive a packet from some random source, and you can't identify them, or you haven't gotten the handshake that says, yes, I know who you are, and yes, we have cryptographic shared variables, if you're not satisfied, you throw the packet away or send back a rejection notice. I expect devices to do that. I think that a responsible design is to inhibit the device from doing anything which it doesn't think is safe, which means don't talk to people that you can't identify.

So I think that we are moving back towards the end to end principle and with the philosophy that you don't have to communicate with some device that you don't recognize. And in fact, you should enforce that. And I think that will actually improve some of the safety and security on the network.

MARK: Fantastic. I'm just keeping a very close eye on the time. So we've been talking about very serious stuff, and I want to make sure we throw in some more fun things in here as well. Noticing about how the planning that you put into place when you first this whole network, and the planning that you've had subsequently since, about looking to the future, I'm curious to know, what's been the most surprising or possibly the most whimsical thing that you've seen happen on the internet, that you were like, that was never-- like, I never thought that was going to happen.

VINT: Well, let's see. Certainly, to be fair about this, I think the arrival of a worldwide web was quite a surprise. I had seen something similar to it that Douglas Engelbart developed and demonstrated as early as 1968. In fact, if your listeners would like to go online and Google the mother of all demos, you will see something quite astonishing, which is the demonstration of a kind of world wide web in a box, in one machine, at SRI International in Menlo Park, California.

Much of the world wide web is picked up in that particular demonstration. He had hyperlinking, for example, of documents produced in the online system. He had built a mouse, so that you could point to things on the screen and click on them, and say, pay attention to that, or go to that document, or perform an edit to this document at the place where I am pointing. So he had to invent the mouse. He invented portrait mode displays, which made things look more like a sheet of paper than the sort of yellow on green displays that were common of the day.

So Tim Berners-Lee, of course, comes along in late 1991 at CERN, in Switzerland, with an expansive network-based idea for a similar thing. I'm not sure whether he even knew about the online system from Engelbart at the time. And of course this evolves into Netscape Communications product, with the follow on to the Mosaic browser. And it suddenly triggered this avalanche of content being created by people who were able to either write their own HTML or had an application that did that for them.

I was totally blown away by the amount of content that suddenly showed up on the net that people just wanted to share. They weren't asking for any kind of compensation at all. They just thought maybe people would find what I know interesting to them. And so I'm seeing this pile of stuff just flowing into the net in the mid 1990s, thinking--

And then, of course, Google comes along with its search engine, following Altavista and Archie and several other things, Yahoo and so on, which helped to try to make sense out of this increasing pile of content. I was amazed that people would share so much information without expectation of compensation. And I'm pretty sure they were doing it for the satisfaction of knowing that what they knew might be useful to somebody else.

I think there is this secret desire in all of us to believe that we've done something that's useful for someone else. We've shared something that's helpful to someone else. And the internet is a perfect medium in which to try to do that. So that certainly surprised me.

Now, as far as things-- funny things, well, of course, when the first internet picture frame showed up, I remember thinking, what? What do you mean the internet enabled picture frame? What does that mean?

And of course, people said, well, it downloads images from a website and then cycles through them. And that means the grandparents can see what their grandchildren are doing when they get up in the morning. They just look at the picture frame, and it's just updated itself from the latest website. And that surprised me.

On the other hand, I do remember in the-- I think it was probably in the early 1990s, there was a-- or maybe late '80s-- there was a convention or an exposition called Interop, which stood for interoperability, that was started by a friend of mine, Dan Lynch.

And during one of the Interop shows, somebody decided to put a toaster up on the network, so you could send an SNMP control packet saying how burned you wanted your toast. And we were all saying, oh, isn't that funny? Ha, ha, ha. And someday, everybody will have the internet-enabled devices on them.

Well, now, here we are. The internet of things is rapidly flowing on us. But I remember, at the time, we were all thinking that would be pretty funny.

I used to make jokes about oh yes, someday every light will have its own IP address. Well, guess what? You know, Phillips makes an internet-controlled light bulb, as do others, I suppose, and they all have their IP addresses. So don't make fun of things, because who knows, they may come true.

So those are some of the things. And I suppose the obligatory observation, I never expected as many cat videos to show up on the net as have. Who spends their time watching cats?

FRANCESC: OK, so you mentioned Tim Berners-Lee and the world wide web. And as part of the research for this episode, I cannot force asking this question. I've seen a picture of the two you, wearing both t-shirts, where you're wearing a t-shirt that says, I did not invent the web. And he's wearing a t-shirt saying, I did not invent the internet, which is by itself an amazing t-shirt. But I think the important part here is that it is the only picture ever, I've ever seen of you, not wearing a suit.

VINT: Oh, yes. Right. Well, and I kind of pulled that over my coat.

MARK:

FRANCESC: Of course.

VINT: So there's a story about the three-piece suits, if you want to finish this interview with that story.

FRANCESC: Absolutely. Yes.

VINT: All right, so this is a very simple story. I'm at Stanford University. I've been running the internet research program from there as an assistant professor. And the Advanced Research Projects Agency says, why don't you come to Washington and just run the whole thing, and run the packet satellite program and the packet radio program and the packet security program along with internet.

So I agree, and my wife who's from Kansas, but who was with me at Stanford, says, you're going to Washington, or we're going to Washington? Three-piece suits. So she goes out and she buys three three-piece suits from Saks Fifth Avenue at the Stanford shopping center, including a seersucker three-piece suit, because she knows it is going to be hot and humid during the summertime in Washington.

So I show up around August or so at ARPA, and the next thing I know, I'm asked to go testify at some committee at the Congress, and I'm wearing my three-piece seersucker suit. So I show up, and I do my testimony, and I go back to ARPA. And weeks go by.

And one day, the director of ARPA calls me into his office and says, I want to talk to you about your congressional testimony. And I'm thinking, oh, did I screw up? Am I about to lose my government job? Is it the end of the world?

And so I sit down, and he says, oh, I have the letter from the chairman of the committee in front of me. He says thank you very much for Dr. Cerf's testimony. By the way, he's the best dressed guy from ARPA we've ever seen. And I took that as positive feedback, so I've been wearing three-piece suits ever since.

FRANCESC: That is amazing. That has not changed. Yeah. I think you are still probably the best dressed person in tech that I know.

VINT: Well, I ought to tilt my camera here, so that you can see that I am indeed wearing a three-piece suit here, in my Washington office.

FRANCESC: I'm so happy I am recording this right now. [LAUGHS]

MARK: For those who are listening on the podcast, Vint is wearing a three-piece suit right now.

VINT: Well, actually, it was very appropriate to wear a three-piece suit in any case, as I was at the Inter-American Development Bank with a whole lot of very senior people. And so I think it's a sign of respect to show up well dressed when you're speaking to people who are more important than you are.

FRANCESC: I'm so sad right now that I am wearing just a t-shirt.

[LAUGHTER]

MARK: Well, Vince, unfortunately, we are running out of time. I would love to spend more time chatting with you, but I really appreciate you taking the time out of your day to chat with us and come with us and celebrate our 100th episode. It's been absolutely lovely and a complete delight speaking to you today.

VINT: Well, thank you so much for that. I am looking forward to spending more time with the Google Cloud team. And as you know, we are making some very serious investments, not only in the increased scale, but also new diversity in the system. So as time goes on, we are going to see not only our conventional CPUs, but the Graphics Processing Units, the GPUs, and now increasingly, the TensorFlow processing units for doing multilevel neural networks. And eventually, assuming we're successful, we will have quantum processing units that will allow people to do things faster than they ever could before for certain kinds of optimization.

So the system which started out being a warehouse computing commodity commonality is now going to become a much more diverse computing platform that can specialized to solve particular problems that our customers have. So I'm very excited about this new heterogeneous computing environment that Google brings to its customer base through the Google Cloud.

FRANCESC: That is definitely very exciting. And if you want to come back to the podcast and tell us more about it, we're definitely, definitely down for that.

VINT: I'd be delighted to do that.

MARK: Any time. All right, well, thank you so much.

VINT: OK.

FRANCESC: Thank you very much. Goodbye.

VINT: See you guys on the net.

MARK: Oh my god, we just interviewed Vint Cerf. This was amazing.

FRANCESC: Oh my god.

MARK: Career highlights.

FRANCESC: We've got to admit that we've been maybe just talking about how happy we were for the last 20 minutes. [LAUGHS]

MARK: Yep. So I want to say, definitely. This is episode 100, to all our listeners, to all the people who have downloaded our podcast, to all the people who have wandered up to us and said hello, thank you so much for listening to us. By you doing that means that we were able to interview Vint.

FRANCESC: Yes. Also, thanks to Vint Cerf.

MARK: Yes.

FRANCESC: Yeah. Thanks--

MARK: I'm still so giddy.

FRANCESC: Yeah, I know. This was amazing. Like a huge opportunity that I would have never expected to have. And it was because a long time ago, October--

MARK: 2015.

FRANCESC: 2015?

MARK: Yeah.

FRANCESC: We got together in a meeting, and you went, why don't we do a podcast? And I was like, OK. Whatever.

MARK: Sure. Yeah.

FRANCESC: And a year and a half later, we interviewed Vint Cerf.

MARK: And we have 100 episodes. Actually, it's two years. It's been two years.

FRANCESC: Two-- oh my god. I'm old.

MARK: 52 weeks, weekly episodes. It's been two years.

FRANCESC: We're not going to go over our favorite moments of the whole podcast, because right now, it was this episode, clearly. Without losing any respect for all of the amazing episodes we've done before, thanks so much also for all of the guests that we've had over those 100 amazing episodes.

MARK: Yes.

FRANCESC: I feel like there's one that deserves an extra mention because we've had him so often; Paul Newson. So Paul Newson, thank you so much for recording-- I feel like it's been four episodes, at least. We have a section. We have a category of the podcast which is Paul Newson. Thanks to him, too.

MARK: No, absolutely. And we should also make mention to a decent chunk of people who work behind the scenes who have also made this possible; Greg, our manager, Shana, who runs social, Neil in marketing. I'm probably going to miss someone. Sean and James, who are our editors.

FRANCESC: Exactly. Don't forget our editors.

MARK: Our editors are amazing. They do a wonderful, wonderful job. If I've forgotten anyone, I'm deeply apologetic, but you're all incredible. Did I miss anyone?

FRANCESC: I don't think so. And if you did, now I feel apologetic too, because I don't know anyone else.

MARK: Definitely, you all helped so much. And we are so, so, so very thankful.

FRANCESC: I feel like to celebrate our 100th episode, since we got this amazing episode as a present to our audience, I feel like our audience should give us a present back.

MARK: They need to get in contact with us.

FRANCESC: Yes, they should send us selfies. A 100th episode selfie or something.

MARK: Yes.

FRANCESC: Yes.

MARK: Yes. Yes.

FRANCESC: Pictures of puppies, too, are also very good.

MARK: Yeah. How can they get in contact with the podcast? You know you want to do this.

FRANCESC: Oh, we're going to do that. OK. So you can send us your selfies via email at--

MARK: Hello@gcppodcast.

FRANCESC: You can send us your selfies via Twitter.

MARK: At @gcppodcast.

FRANCESC: You can send us your selfies on Google+.

MARK: At plus@gcppodcast.

FRANCESC: You cannot send those selfies through our website because we do not have a form, but it's--

MARK: gcppodcast.com.

FRANCESC: And if I remember correctly, you can also send us selfies on Slack.

MARK: #podcast on bit.ly/gcp-slack.

FRANCESC: Oh, one more. Reddit. Reddit. Reddit. I forgot about it.

MARK: Reddit/r/gcppodcast.

FRANCESC: Awesome. So yes. Send us your selfies. We're just curious to know what are your happy faces while you were listening to this episode.

MARK: Yeah, please do. Well, Francesc, I know you're exhausted. It's a late night where you are in Paris. It's a very early morning where I am in Melbourne, Australia.

FRANCESC: I am currently retired, and I have a burger waiting for me.

MARK: Yes. But thank you to you for joining me for 100 episodes.

FRANCESC: Thank you, Mark, for joining for 100 episodes. To be honest, it is not as bad as it sounds. They was very fun.

MARK: It was-- oh, thanks. Thanks. [LAUGHS]

FRANCESC: [LAUGHS]

MARK: Wonderful. All right.

FRANCESC: Thank you. Thank you, Mark. Thank you all for listening. And talk to you all next week, for episode 101.

MARK: Yeah. See you all next week.

FRANCESC: [LAUGHS]

Hosts

Francesc Campoy Flores and Mark Mandel

Continue the conversation

Leave us a comment on Reddit