Descartes Labs with Tim Kelton

Descartes Labs is creating an incredible living atlas of the world from huge datasets leveraging the power of Google Cloud Platform and Tim Kelton, one of the co-founders of Descartes Labs, is here to your cohosts Francesc Campoy and Mark Mandel all about it.

About Tim

Tim is a co-founder of Descartes Labs focuses on building distributed systems using cloud architecture to better see how the earth changes every day. Prior to Descartes Labs, Tim was a Research and Development engineer for 15 years at Los Alamos National Laboratory working on problem areas such as deep learning, space systems, nuclear non-proliferation, and counterterrorism. In his free time, Tim enjoys mountain biking and skiing in the mountains above Descartes in Santa Fe New Mexico.

Cool things of the week

- Check the transcripts for every episode!

- All Google Cloud Platform episodes on YouTube

- gRPC Project is now 1.0 and ready for production deployments blog post

Interview

- Descartes Labs home page

- Advancing the science of corn forecasting Medium

- Maglev: A Fast and Reliable Software Network Load Balancer Google Research

- Preemptible VMs docs

- Managed Instance Groups docs

- Celery: Distributed Task Queue homepage

- “Tatooine” then and now from space: 40th anniversary of filming of Star Wars Medium

Some maps

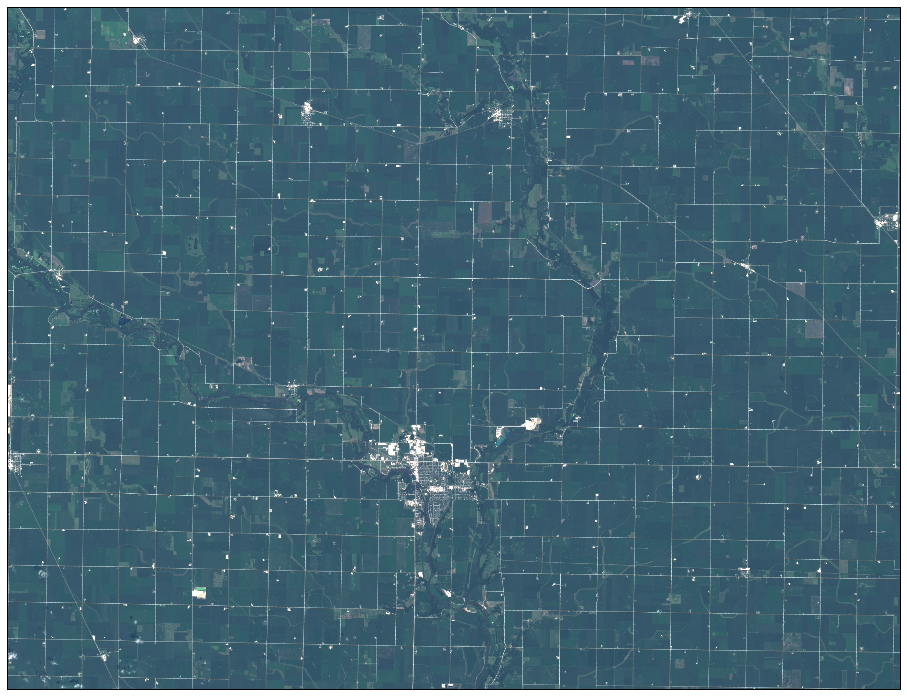

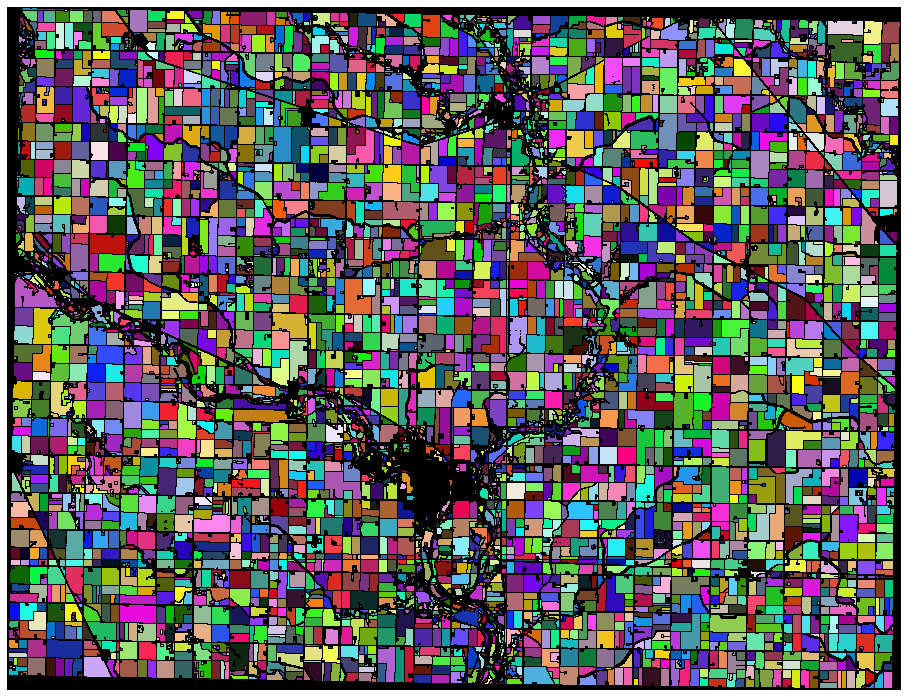

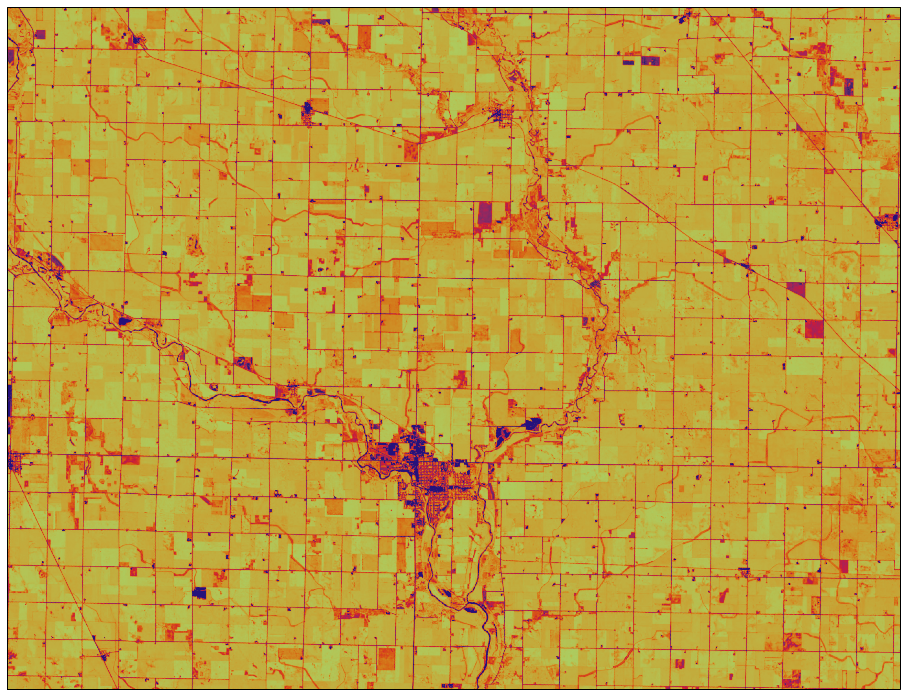

Three maps of Humboldt, Iowa in July 2016.

Cloud free image in true color

We detect fields automatically, using machine learning. This is a map of all the fields in Humbolt.

Vegetative health (using NDVI)

Question of the week

What can you get for free on Google Cloud Platform?

- App Engine pricing

- 28 free instance-hours per day

- Cloud Datastore pricing

- 1 GB of storage

- 50k Entity Reads

- 20k Entity Writes

- 20k Entity Deletes

- Vision API pricing

- 1k units/month (a unit correspond to a feature e.g. facial detection)

- BigQuery pricing

- Loading, Copying, and Exporting data is always free

- First TB of processed data in queries is free every month

- PubSub pricing

- First 250M Operations: $0.40/Million

- First 250M Operations: $0.40/Million

Transcript

show full transcriptFRANCESC: Hi, and welcome to episode number 41 of the weekly Google Cloud Platform podcast. I'm Francesc Campoy, and I'm here with my colleague Mark Mandel. Hey, Mark.

MARK: Hey, Francesc, how are you doing today?

FRANCESC: Doing great knowing that I beat you yesterday at ping pong.

MARK: And I beat you twice. So there you go.

FRANCESC: Yeah, OK, whatever, let's forget about that.

MARK: [LAUGHS]

FRANCESC: So, I'm very happy today because we're going to be talking with Tim Kelton from Descartes Labs, or "Des-car-tez" Labs, depending on how good your French is or not. And he's going to be telling us about how they use Google Cloud to do maps.

MARK: Yeah, he is. It's a really interesting story around, particularly preemptible VMs actually.

FRANCESC: Yeah, preemptible VMs, and really, really, really big data sets.

MARK: Really big data sets, yeah.

FRANCESC: So, yeah, very excited about that. I really enjoyed talking to him, so I hope that you will also enjoy the interview. And then at the end, we will have a question of the week.

MARK: Yeah, we're going to talk a little bit about what you can get for free.

FRANCESC: Yeah, which is always good. Free stuff is good. So, concretely, what are the products, or features, or APIs that you can use for free up to a given point? So what products have free tiers in Google Cloud Platform?

We're going to be discussing them a little bit, not giving all of them because there's too many products, but to give you an idea of what you can do for free basically.

MARK: Yep.

FRANCESC: But before that, we have the cool thing of the week. And as usual, it is the cool things of the week.

MARK: I think we should just rename the section "Cool Things--"

FRANCESC: Yeah, we should just rename it.

MARK: --of the week.

FRANCESC: Yeah, so the first one, the two first ones are actually related to the podcast is a metacool thing of the week.

MARK: Yep.

FRANCESC: The first one is we got transcripts.

MARK: Yeah, which is really cool. So now we get automated transcripts coming through. There will be at least 15 out because that's how many I have right now on the website available. But we'll be gradually increasing that to increase all of them. So, if you want to see the text or read the actual podcast, it's pretty cool. You can do that. And the other thing is the thing you built as well.

FRANCESC: Yes, so, I've been working on it for a couple days. And it involves FFmpeg, and Docker, and Go, and lots of pain. But now we will be releasing every single episode from the Google Cloud Platform podcasts to YouTube. So that's going to be pretty cool.

I already posted three of them, but they're still not public. But by the time this episode comes out, probably everything will be out. So go check it out. We'll have a link to the playlist from the show notes.

MARK: Yeah, I think this is actually kind of cool because if you subscribe to YouTube videos, you can do that anyway. So it gives you another avenue to subscribe to the podcast. But if you're a YouTube Red or Google Play Music person, who owns a subscription to that, it means you can download them for offline use too.

FRANCESC: Oh.

MARK: So you can actually listen to it much like you would a regular podcast.

FRANCESC: Nice. Yeah, I didn't think about that. That is cool. And yeah, I'm actually very excited also about the transcripts because I got an email a long time ago at the beginning about the podcasts from someone saying that they had problems understanding English. And they would rather have the written version of it.

MARK: Yep.

FRANCESC: Cool, perfect, we have that now.

MARK: Awesome, perfect.

FRANCESC: And then we have non-metacool thing of the week, an actual cool thing of the week, which is gRPC had the version 1.0.

MARK: Yeah, this is really cool. I'm a huge, huge fan of gRPC, which is a remote procedure call framework that came out of Google that's open source. Yeah, it's been kind of under development for a while. But it has now hit 1.0, which means there's a lot more-- they've improved the performance of it. Installing all the tools is now easier.

My favorite thing actually is they've released a performance dashboard that's available. You can go look there and see what sort of throughput you can expect to get with different language comparisons because gRPC supports about 10 different languages.

FRANCESC: Yeah, that is nice. Yeah, I also saw that there's a bunch of people using it from open source projects like [INAUDIBLE] or containerd, and CockroachDB. But also companies, I think that the biggest one that is using it is Netflix and Google.

We actually have APIs that only work with gRPC already like BigTable. And then there's other APIs that have both REST and gRPC APIs. Yeah, check it out. We'll have links to the announcement from the show notes.

MARK: Absolutely. Cool. Well, that sounds all really awesome. Why don't we go talk to Tim?

FRANCESC: Yeah, let's go that.

MARK: Sounds good. It's my distinct pleasure to announce that we are joined today by a gentleman by the name of Tim Kelton from Descartes Labs. How are you doing today, Tim?

TIM: I'm doing really good.

MARK: Excellent. Thank you so much for joining us today. I'm pretty excited to be talking to you. I think the stuff you do and the company you work for do some really interesting stuff. But tell us a little about you, and who you are, and what you do, and that kind of stuff.

TIM: Sure, I'm an engineer and part of the founding team here at Descartes. And my main focus is Cloud architecture and then building and scaling what we call our Cloud supercomputer, which is basically a forecasting platform.

And so I end up using a range of Google Cloud Platform tools to accomplish this goal. And that's mainly to see how the Earth is changing every single day. And before Descartes, I was a research and development engineer for 15 years at Los Alamos National Laboratory. And there I worked on a wide range of projects, but was focused around deep learn. The most recent project that lasted about six years was focused around deep learning and applying deep learning to real world problem areas like satellite imagery. And then a portion of that team left Los Alamos to start Descartes.

FRANCESC: Cool. So, you mentioned that Descartes Labs, it allows you to see how the Earth changes? What does that mean?

TIM: Yes, so, we're building a living atlas of the world. And how we're doing that is we're applying machine learning with massive scale data sets, such as satellite imagery, also data sets like global weather, pricing, [INAUDIBLE] truth, even customer data. And then we feed that into our forecasting platform.

And then we can build our machine lot-- excuse me-- machine learning models, and constantly try and improve those models. And this allows us to not just see what's happened historically, but also it lets us forecast into the future.

Kind of interestingly enough, we mainly are focused on areas that humans just could never scale to do, things like global scale food production. You just couldn't get enough people on the ground counting how productive a field is all over the world. It just isn't scalable. So we're using satellite data in that way. And it's really exciting.

We're only 20 months old. So it's a really early stage company. But we're moving really quickly.

MARK: So, exactly how much data are you talking about? Are you talking about satellite imagery and forecast weather? I mean how big are these data sets?

TIM: Yes, so, the data sets vary. Right now we currently have compressed around 3 and 1/2 petabytes of data that we're storing in Google Cloud Platform.

MARK: Oh, only a couple of petabytes. It's fine.

TIM: Yeah.

MARK: That process, that's over a number of years? Is that recently? What's that time series as well?

TIM: Yeah, that's an interesting area. As most people that do machine learning or use tools like Caffe or TensorFlow can tell you, a really big challenge with machine learning tools is having an accurate set of data to train the models and then improve the model's accuracy. And when you're doing things like looking at the Earth, having a really large time window of data helps out a lot.

And often, with satellite data, training sets can be extremely varied. And things like weather cycles are not just repeatable year after year. They vary quite a bit through time.

So the longest continuous observations of the Earth came from NASA's Landsat constellation. And that was launched in 1973. And that's actually available on, thanks to the Google Earth Engine team, on Google Cloud.

And so our first big project really early on in the company was, we basically saw we needed a lot of back test data to be able to test models throughout time. And we basically processed 43 years of this NASA Landsat imagery. So in pixel terms, that's going to be 2.8 petapixels of data. In data terms, that's about a petabyte of data.

And so we did all of that on Google Compute Engine. And that was about just a little under 16 hours. And that's using 30,000 virtual CPU cores. And that was all on preemptible VMs. So it was quite sizable.

And I should say that as impressive as Google Compute Engine scaling up, probably the most interesting part to us was GCE's network and how well their network actually scaled. We were actually seeing for most of that 16 hours, over 20 gigabytes a second going into Google Compute Engine and then over 8 gigs in parallel going out of Google Compute Engine.

And we've worked in places-- most of us come from Los Alamos or have worked on other large-scale supercomputing clusters. And those types of numbers are on par with anything you would see in a high performance supercomputer system today. So, we basically are using Google to build the same types of systems that we were used to working with.

And Google recently actually had a paper about their networking called, I think it's "Maglev." And so that was a really fascinating-- as an end user, we saw how it scaled. And that was really interesting. But then reading the paper of how all those components were built together was pretty fascinating.

MARK: So you were processing that entire petabyte data set during that time?

TIM: Yeah, we were running that all through our processing pipeline.

MARK: How much, around abouts is that cost? I mean, you talked a little bit about preemptible VMs there, but--

TIM: So preemptibles dramatically reduce your costs, if your workload doesn't need to last over 24 hours. So for this use case, our whole goal was to get it done in under a day. And they were great for that.

When we ran this in early 2015, the cost for just Compute was just under $10,000. But then I recently just looked at the-- there was recent pricing drops in Compute Engine. And so those prices now would be about $3,600. So that shows the difference in pricing.

That's not the data storage. The data storage was a little bit more than that.

MARK: But they go through a petabyte. That's not too shabby.

FRANCESC: That is pretty amazing actually. So you mentioned real quick about preventable VMs--

TIM: Preemptible?

FRANCESC: What did he say?

TIM: You said preventable.

FRANCESC: Preventable. No, preemptible VMs. Sorry. Why did you choose them? What is the big thing? I understand that it is more affordable than the normal VMs. But what kind of restrictions and what kind of design decisions did you take into account?

TIM: Yes, so preemptibles, at maximum, will only last you for 24 hours. And so you need to be processing some sort of processing task that's going to obviously last less than that. So you're not going to run a production web server or database server on that. But for really large processing workloads such as machine learning, model training, having a lot of pre-processing pipelines, they're a great use case for that.

For us, we use asynchronous task queues to load data or the processing we were going to do into the task queue and then connect up all these preemptible instances via instance groups. And then you can scale up and down the instance groups. And now you can scale up and down the instance groups inside of those different regions. So that's quite useful.

MARK: Cool. So you were able to leverage the power of preemptible VMs to basically reduce your costs more than anything else.

TIM: Yeah, it's a huge cost reduction compared to just running a regular VM for a few hours. So we use them quite heavily in all of our processing pipelines now as a cost reduction. But also, with machine learning, a lot of times you're training and retraining a model to try and improve your accuracy. So we have a lot of really large-scale bulk workloads.

And we've kind of taken the road of not going down the path of using something like Hadoop or things because we have a lot of C, and C++, and Python code. And so instead, we basically use Google Cloud Storage as our large distributed file system. And we know that will scale way beyond our current needs.

And it has really, really fast network access from Compute Engine. So we can connect real quickly. And so it has a lot of benefits too, over trying to get a C, or C++, or Python code to work inside of something like Hadoop.

MARK: So, the issue obviously, or maybe not obviously, but the issue with preemptible VMs is they could shut down. How do you deal with that happening? Is there a retry mechanism you use? Or how do you deal with that?

TIM: Yeah, we use some pretty basic open source task queues. We use a Python queue called Celery. And that has a back end persistence store. You can configure a bunch of different ones. We use Redis. We're pretty big fans of Redis.

And so we write all the tasks into the queue. And then basically, if they still are not done within a certain time, you can retry the tasks or rerun certain tasks over again and make sure you've processed all of your work. Our workloads are, in many situations, they've kind of fall into this embarrassing parallel problem.

FRANCESC: So, you mentioned that you were using asynchronous tasks. Could you talk a little bit more about that? Are you using Pub/Sub? Are you using task queues? What kind of product are you using?

TIM: Yeah, we just use an open source library. It's called Celery. It's a Python library. And that has configurable back ends. And on that back end we use Redis in memory. And that's all just running on a regular-- that's on our non-preemptible instance because we do not want that to go away.

And then for monitoring, we use the stack, the Redis Stackdriver agent. And that keeps track of how many concurrent connections and how much load for our various threads on the Redis cluster it's running there.

That's kind of a great way to see if there's a sudden spike or a change. When that's your central hub that all your work runs around, you need that to really be up and be reliable.

MARK: Cool. So we talked a bit about, obviously, that initial data set. I'm guessing you have ongoing data that's coming in now. As your company's expanded, you have more and more information coming in on an ongoing basis. Would that be right?

TIM: Correct. We're processing data probably right now as we're talking. We're basically constantly ingesting new data in our processing pipelines, literally from hundreds of different satellites not just those eight NASA Landsat satellites. Right now we're at about 3 and 1/2 petabytes of compressed data. And a lot of that's public satellite imagery that's open, NASA, European Space Agency, various people like that. But then we also have private partners as well.

And so we're constantly, as we get new updates to various geographic regions, or we're working on a new problem case maybe inside of agriculture, or studying a new crop that's in a different part of the world, we'll look at different sets of imagery that we might not always hit every single day.

We have about five terabytes a day that just constantly flows in. And that varies from day to day. But in the future we're expecting this to basically be over 30 petabytes in the next year and a half. And that's kind of a cool thing in space right now, or in space and technology.

Most of your listeners probably watch YouTube videos of SpaceX and SpaceX landing rockets on a floating barge in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It's pretty awesome. But from a cost perspective, a big part of your cost to getting satellites up into orbit is actually the rocket launches and making them reusable. And at the other side of that, you have smaller and smaller satellites. And so they're made with more and more commodity parts. They're often called CubeSats. An example of that would be a Silicon Valley startup up called Planet. Or Google has a team called Terra Bella. And they have what they call a small sat.

So you have that on the other end. So we're going to get more and more sensors in the next few years going up into space, seeing the Earth every single day. And teams like ours will be able to look at how the Earth is changing every single day instead of people manually downloading an image and trying to compare one to one.

FRANCESC: So going back to your stack, what is the thing that is running on your preemptible machines? Are you running just Python directly there? Are you using containers? What kind of jobs do you run?

TIM: We use both raw code. We use startup scripts in the GCE instances. And we use containers on some of the more involved configurations that we want to maintain consistency and make sure running tested version of the code is operating in a way we're expecting. We'll use startup scripts with instance groups so they could either connect to Google Container Registry and pull the container down. Because that's really, really quick access to pull that container because it's just sitting in Google Cloud Storage inside of our project. Or, if we run a startup script, then you're kind of just defining scripts to run and install. But most of our workload is as Python, or C, or C wrapped in Python, Cython for most of our workloads. And I think that's pretty-- Python's a pretty popular language in machine learning world these days.

MARK: Cool. I'm actually really curious. You've probably looked at more satellite data than maybe a lot of people. I'm kind of curious to know what are the most interesting things you've managed to find out about the planet or society as a whole? What have you seen in those imagery that's been really interesting?

TIM: Whoo, that's a tough-- you see all types of random things. The funniest, maybe not funny-- it is very obvious after a while. You don't realize how cloudy the Earth actually is in many times of the day. Often, when you're trying to find an image, if there's a big sporting event or something like that. And you have a cloud actually blocking. So we actually have a technique for being able to process and fuse together many different scenes to remove the clouds over time.

But yeah, I don't-- I'm trying to think of something really, really bizarre I have seen. One of our co-founders, he actually located the spot that and the time when the original "Star Wars" movie, where it was actually filmed.

He went all the way back and found this-- because we have this massive archive, basically since 1973. And so he found all the exact images from that location.

MARK: That's pretty cool. I guess more day to day, I know you do a lot around like food yields as well, I think. Is that right?

TIM: Correct. Our first main products are actually focused a little bit more in agriculture and basically modeling the global food supply. We look down on the Earth, and we can see various fields all across a growing region. Not just a small county, but we could see a whole state, or a whole country, or even the whole globe. And we can see that every single day.

So organizations like the US Department of Agriculture will manually send out surveys to farmers. And they'll get a small statistical sampling of the population and how the food production is growing. But we basically are seeing every field all across the globe every single day and taking a measurement of the actual health of the fields. And so that allows us to not just classify the fields and what they are, if it's a corn field, or a soybean field, or wheat field, but also to be able to look at how much is that field going to produce and what's our estimate. And that leads us into what we have as more of a forecasting product.

FRANCESC: That is actually very interesting. Do you use any kind of forecasting to be able to predict things like, well, given the kind of fields we have, and given the weather forecast that we have, there's going to be lack of food in some country in a couple months, something like that. Is that something that you've ever used?

TIM: I don't think we're going that far down the analysis, like is there going to be famine outbreak in country x or y. It's definitely something that could be possible. Right now, we're looking at overall yields. There's obviously a lot of how much production of corn might there be in the United States in this growing season, or in South America during this growing season.

But longer term, we're hoping to expand to more and more crops and more and more geographic regions basically. And we also actually have a new mobile app that we've built. We're using that. We actually built it on Firebase. We have an iOS and Android app.

And anyone can actually pull that down and see our delayed forecast. It's not in real time. It's a week behind. And they can actually use that to look at that location and see what we're predicting to be the yield of corn say for that given county in Iowa or someplace like that.

And you can even vote. And you can say, well, we actually think you're totally wrong. Or yes, that seems about right. And you can provide feedback there.

MARK: Cool. All right. That was really great. Before we wrap up here, is there anything else you want to mention? Maybe something we've missed or something you want to mention or plug?

TIM: That's the main things. Moving forward, we're hoping, we're really excited about some of the new changes on Kubernetes and being able to actually run jobs and then having auto scaling on jobs. So we are hoping that more and more of our daily processing pipeline will be able to work that way. So that's pretty exciting.

And then we should be having more and more updates, obviously, with our mobile app and our website. So if you're excited about corn yields or soybean yields, you'll be able to key in on that. I'm not sure what we're predicting in the Bay Area. I'm guessing it's pretty minimal right now.

But yeah, we'll constantly have new updates. And will always be improving our models and working to try and make them more and more accurate and use that large set of data to improve the accuracy in our forecasts.

FRANCESC: Excellent. Great. Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us and tell us about so many cool predictions really. That was really, really interesting.

TIM: Well, thanks, guys. I enjoyed it.

FRANCESC: Thanks again, Tim for such an amazing interview. I learned a lot about how you can manage such huge amount of data with preemptible VMs.

MARK: Yeah, it was super, super cool. And just the large amount of storage and the amount of data that they have moving around their system at any given point in time is pretty incredible.

FRANCESC: Yeah, it is pretty amazing. We'll have links. Actually, we'll have images in the show notes so you can have an idea of the kind of maps they generate, if you're curious about it. But now it's time to go with the question of the week. And the question of the week, I'm not sure where it comes from. But I know that I had it in the last GDG in San Francisco, which is about Google Cloud Platform.

One of our coworkers, Terry, gave a talk. And at the end, someone asked, OK, so what are the things I can do for free on Google Cloud Platform? And the first part of the question is, well, when you sign up for Google Cloud Platform, your get already $300 that are valid for two months.

MARK: Yeah, 60 days.

FRANCESC: Yeah, 60 days. So with that you can do many things. $300 is a decent amount of money. You can run many instances for quite a while.

MARK: Yeah, I didn't really say people will probably run out of the 60 days before they run out of the $300, generally speaking.

FRANCESC: Generally speaking, yeah, unless you go and you start like 32 course instance and stuff like that. This is like a little bit more-- but otherwise, yeah, you should be fine with that. But even without signing up and actually going to the free to trial, there's also some products that allow you to have a free tier that is there forever, no limit of time. So you can just be there and use it for free. And I actually do it all the time.

One of them is App Engine, which is one of my favorite ones. So the free a 28 free instance hours per day.

MARK: So slightly, you can get like one point-- I'm not even going to the math-- slightly more than that. [LAUGHS]

FRANCESC: I think we all know how you--

MARK: I don't do things in my head. [INAUDIBLE]. Yeah, so slightly more than a day for a frontend instance.

FRANCESC: Yeah.

MARK: --that's available to be used.

FRANCESC: And the good thing is that most of the time you're actually going to use way less than that because if you don't have that much traffic, the instances will shut down automatically. So in general, that is way more than enough to do your personal projects and stuff like that. So that is pretty awesome.

And once you have that, it is like, oh, so, do I have access to any other free things? I need to store data. Well, you can use the data store for free. There is, I think it is the first gigabyte, right? Yeah, there's like a first gigabyte of storage is free. And then you can do up to 50,000 reads, 20,000 writes, and 20,000 deletes. And that is per day.

So 50,000 reads per day, it is decent amount of traffic. So you can check it out. Also, you get some other things like mail, and your fetch, and task queues. There's also different levels of free tier for those.

MARK: Yep. And it's worth noting now with data store, it's not just tied to App Engine anymore. So if you're using Datastore outside of App Engine, you still sit into that free tier as well.

FRANCESC: Oh, yeah, you can use the REST API and get that free tier also. What else?

MARK: So, there is also a BigQuery, one of our most favorite to big data processing tools that gives you the first terabyte of data process per month to be free.

FRANCESC: Nice.

MARK: Which is really cool, especially if you're playing with any of our public data sets and you want to have a go with some of those to see what's possible. You can do a fair bit of processing without having to worry about paying for it.

FRANCESC: And even if you don't want to use the public data sets, you can also upload yours. You don't pay for uploading data. You pay for how much data you are actually storing. But it's only $0.02 per gigabyte per month. So you can get started quite easily for not very much, especially taking into account that you get those $300 for free. $300 divided by $0.02 is a lot. Yeah.

MARK: Yeah, yeah, don't--

FRANCESC: Let's go with a lot.

MARK: Let's go with a lot.

FRANCESC: Then, what else?

MARK: Vision API.

FRANCESC: Yeah, the Vision API, Vision API, it is really cool. It's one of my favorite APIs because it allows you to do things that basically seem like magic.

MARK: It's magic, yes.

FRANCESC: It's basically magic. And everything you need to know is how to use JSON. So that is pretty amazing.

MARK: Yeah. And it's really cool. So it doesn't necessarily work per image. It works per feature, so you're asking an image say, [INAUDIBLE] label detection or OCR this text. So you could do multiple features per image. But the first 1,000 units per month is free of features. So you can get a decent amount of stuff done there.

FRANCESC: Yeah, I could say that it is not a huge amount. So if you have an application that is actually used, you will hit that limit quite quick. But this is perfect for development.

MARK: Yeah.

FRANCESC: If you're doing development and testing, this is totally fine. And you will probably not hit it any time soon. So that is really cool.

Then we have a bunch of other things that they're not really free.

MARK: But they're cheap enough. Like they round down to zero, I feel like.

FRANCESC: Yeah, like one of the examples is Pub/Sub. Pub/Sub is 200 million operations, it is $0.40. So basically, one billion operations is about one coffee.

MARK: I like that. We should do more stuff like per coffee.

FRANCESC: Actually, it really depends. If you're drinking coffee in San Francisco, it is like half a coffee. Yeah, so, yeah, there's a bunch of them. They're really, really, really affordable. So we have a link. We'll have actually a table with a bunch of different free tiers and links to all the pricing pages and everything from the show notes. So if you're interested in this, go check it out. But the most important thing to take into account is basically, if you want to get started, you use the free trial. And you can always get the App Engine plus Data Store, which scale automatically for free up to a decent amount of traffic.

MARK: Awesome. Well, I think that brings us to the end of yet another episode. Are you heading off anywhere? Just for Funk episodes? What are you up to?

FRANCESC: I'm going to edit a Just For Funk episode. And it should come up soon. Also, I'm working on open sourcing the little tool that I wrote to push podcast episodes to YouTube.

MARK: Nice.

FRANCESC: That's going to be fun, yeah.

MARK: Awesome. When this comes out, I will literally be at PAX Dev. I'm going to be attending.

FRANCESC: PAX Dev in Seattle?

MARK: Seattle, yeah. So that'll be good. And then in September, I will be at one of my favorite conferences. I will be at Strange Loop doing a couple of little things there. We'll see what happens. I need to coordinate with some people. But I love that conference. It's loads of fun.

FRANCESC: Sounds fun. Maybe next year I'll attend. Maybe.

MARK: Maybe, we'll see.

FRANCESC: Who knows, yeah. Well, thanks so much again for taking the time to record the new episode with me.

MARK: Thank you very much. And thank you very much to all our listeners for tuning in once again.

FRANCESC: Yep. Talk to you all next week.

MARK: See you next week.

Hosts

Francesc Campoy Flores and Mark Mandel

Continue the conversation

Leave us a comment on Reddit